Scaling Study

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How many resources should be requested for a given job?

- How does our application behave at different scales?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to …

- Perform a scaling study for a given application.

- Notice different perspectives on scaling parameters.

- Identify good working points for the job configuration.

The deadline is approaching way too fast and we may not finish our project in time. Maybe requesting more resources from our clusters scheduler does the trick? How could we know if it helps and by how much?

What is Scaling?

The execution time of parallel applications changes with the number of parallel processes or threads. In a scaling study we measure how much the execution time changes by scanning a reasonable range of number of processes. In a common phrasing, this approach answers how the execution time scales with the number of parallel processors.

Starting from the job script render_snowman.sbatch:

BASH

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=200MB

# The `module load` command you had to load for building the raytracer

module load 2025 GCC/13.2.0 OpenMPI/4.1.6 buildenv/default Boost/1.83.0 CMake/3.27.6 libpng/1.6.40

time mpirun -- ./raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp=128 -png "$(date +%Y-%m-%d_%H%M%S).png"we can manually run such a scaling study by submitting multiple jobs.

In OpenMPI versions 4 and 5 the number of Slurm tasks is automatically

picked up, so we do not set -n or -np of

mpirun. We use -- to separate the arguments of

mpirun – none in this case – from the MPI application

raytracer and its arguments. Otherwise you may experience

errors in some versions of OpenMPI 5, where mpirun

misinterprets the arguments of raytracer as its own.

Scaling other resources with number of CPU cores

When scaling the resources outside of the job script, e.g. with

sbatch --ntasks=X ..., as done above, we make sure to scale

other resource requirements with the number of parallel processors. In

this case, --mem-per-cpu=200MB is necessary, since

--mem results in a fixed memory limit, independent of the

number of processes.

For example, if each MPI process needs \(100\,\)MB, requesting \(2\,\)GB would only be enough for up to 20 MPI processes.

Forgetting a limit like this is a common pitfall in this situation.

Let’s start some measurements with \(1\), \(2\), \(4\), and \(8\) tasks:

OUTPUT

$ sbatch --ntasks 1 render_snowman.sbatch

Submitted batch job 16142767

$ sbatch --ntasks 2 render_snowman.sbatch

Submitted batch job 16142768

$ sbatch --ntasks 4 render_snowman.sbatch

Submitted batch job 16142769

$ sbatch --ntasks 8 render_snowman.sbatch

Submitted batch job 16142770Now we have to wait until all four jobs are finished.

Regular update of squeue

You can use squeue --me -i 30 to get an update of all of

your jobs every 30 seconds.

If you don’t need a more regular update, it is good practice to keep the interval on the order of 30s to a couple of minutes, just to be nice to Slurms server resources.

Once the jobs are finished, we can use grep to get the

wall clock time of all four jobs:

OUTPUT

slurm-16142767.out:real 2m7.218s

slurm-16142768.out:real 1m7.443s

slurm-16142769.out:real 0m32.584s

slurm-16142770.out:real 0m17.480sThe real-time is decreasing significantly each time we double the number of Slurm tasks. From this, we feel that doubling the number of CPU cores really is a winning strategy!

Exercise: Continue scaling study to larger values

Run the same scaling study and continue it for even larger number of

--ntasks, e.g. 16, 32, 64, 128. So far, we have been using

--nodes=1 to stay on a single node. At which point are your

MPI processes distributed across more than one node? Use Slurm command

line tools to find out the how many CPU cores (MPI processes) are

available on a single node. You may have to increase the number of nodes

with --nodes, if you want to go beyond that limit.

Gather your real time results and place them in a

.csv file. Here is an example for our previous

measurements:

ntasks,time

1,127.218

2,67.443

4,32.584

8,17.480

...How much does each doubling of the CPU resources help with running the parallel raytracer?

You can use sinfo to find out the node names of your

particular Slurm partition. Then use scontrol to show all

details about a single node from that partition. It will show you the

number of CPU (cores) available on that node.

ntasks,time

1,127.218

2,67.443

4,32.584

8,17.480

16,10.251

32,7.257

64,8.044

128,8.575Using grep "real" slurm-*.out, we can see the execution

time is halved in the beginning, with each doubling of the CPU cores.

However, somewhere between \(8\) and

\(16\) cores, we start to see less and

less improvement.

Adding more resources does not help indefinitely. At some point the overhead of managing the calculation in separate tasks outweighs the benefit of parallel calculation. There is too little to do in each tasks and the overhead starts to dominate.

At some point adding more CPU cores does not help us anymore.

Adding more CPU cores can actively slow down the calculation after a certain point. The optimal point is different for each application and each configuration. It depends on the ratio between calculations, communications and various management overheads in the whole process of running everything.

Overheads and Reliable Measurements

Many overheads and when they show also depend on the underlying hardware. So the sweet spot may very well be different for different clusters, even if the application and configuration stays the same!

Another common issue lies within our measurements themself. We

perform a single time measurement on a worker node that is possibly

shared with other jobs at the same time. What if another user runs an

application that hogs shared resources like the local disk or network

interface card? In this case our measurements become somewhat

non-deterministic. Running the same measurement twice may result in

significantly different values. If you need reliable results, e.g. for a

publication, requesting exclusive access to Slurms resources through the

sbatch flag --exclusive is the best approach.

As a drawback, this typically results in longer waiting times, since

whole nodes have to be reserved for the measurement jobs, even if not

all resources are used.

Even on exclusive resources, the measurements cannot be 100% reliable. For example, the scheduling behavior of the Linux kernel, or access to remote resources like the parallel file system or data from the web, are still affecting your measurements in unpredictable ways. Therefore, the best results are achieved by taking the mean and standard deviations of repeated measurements for the same configuration. The measured minimum also has strong informative value, since it proofs the best observed behavior.

Keep in mind, --exclusive will always request all

resources of a given node, even if only few cores are used. In these

cases, tools like seff show worse resource utilization

results, since measurements are done with respect to all booked

resources.

Scaling studies can be done with respect to different application and job parameters. For example, what is the execution time when we change the workload, e.g. a larger number of pixels, samples per pixels, or a more complex scene? How much does a communication overhead change, if we change the number of involved nodes while keeping the workload and number of tasks fixed, i.e. changing the network communication surface? Scaling studies like these can help identify pressure points that affect the applications performance.

Scaling studies typically occur in a preparation phase where the application is evaluated with a representative example workload. Once a good configuration is found, we know the application is running close to an optimal performance and larger number of calculations can start, often called the production phase.

In a similar vein, scaling studies can be a formal requirement for compute time applications on larger HPC systems. On these systems and for larger calculation campaigns it is more crucial to run efficient calculations, since the resources are typically more contested and the potential energy- and carbon footprint becomes much larger.

Speedup, Efficiency, and Strong Scaling

To quantitatively and empirically study the scaling behavior of a given application, it is common to look at the speedup and efficiency with respect to adding more parallel processors.

Speedup is a metric to compare the execution times with different amounts of resources. It answers the question

How much faster is the application with \(N\) parallel processes/threads, compared to the serial execution with \(1\) process/thread)?

It is defined by the comparison of wall times \(T(N)\) of the application with \(N\) parallel processes: \[S(N) = \frac{T(1)}{T(N)}\] Here, \(T(1)\) is the wall time for a sequential execution, and \(T(N)\) is the execution with \(N\) parallel processes. For \(2\) processes, we observe a speedup of \(S(2) = \frac{127.218}{67.443} \approx 1.89\)

Efficiency in this context is defined as \[\eta(N) = \frac{S(N)}{N}\] with speedup \(S(N)\) and describes by how much additional parallel processes, \(N\), deviate from the theoretical linear optimum.

Exercise: Calculate Speedup and Efficency

Extend the .csv file of your measurements from above

with a speedup and efficiency column. It may

look like this:

ntasks,time,speedup,efficiency

1,127.218,1.00,1.00

2,67.443,1.89,0.94

4,32.584,3.90,0.98

8,17.480,7.28,0.91

...You may want to use any data visualization tool, e.g. python or spreadsheets, to visualize the data.

What number of processes may be a good working point for the raytracer with \(800 \times 800\) pixel and \(128\) samples per pixel?

For all of our measurements, the speedup and efficiencies are

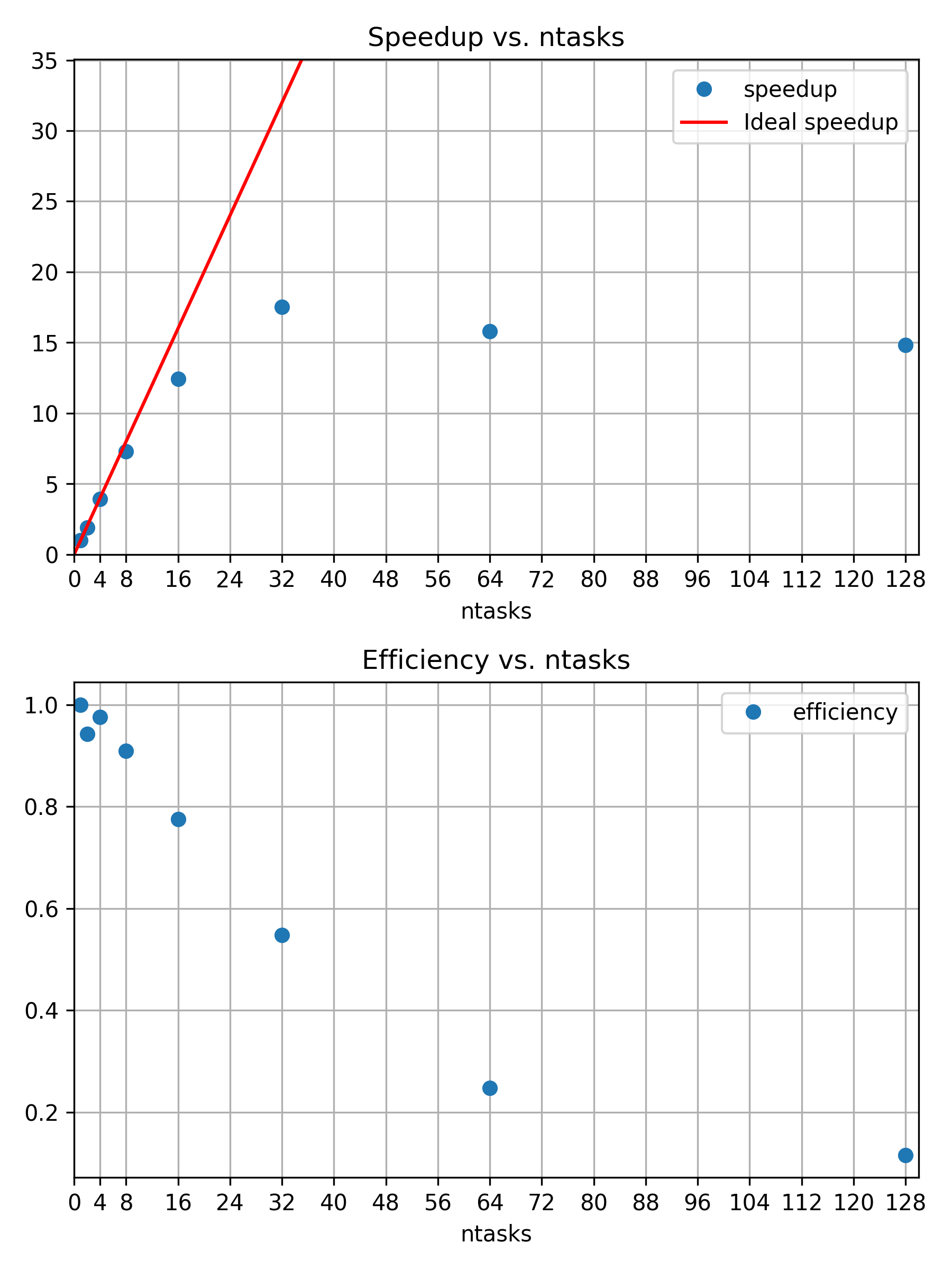

ntasks,time,speedup,efficiency

1,127.218,1.00,1.00

2,67.443,1.89,0.94

4,32.584,3.90,0.98

8,17.480,7.28,0.91

16,10.251,12.41,0.78

32,7.257,17.53,0.55

64,8.044,15.82,0.25

128,8.575,14.84,0.12Plotting the speedup and efficiency helps with identifying a good working point:

The 16th processor is still close to 80% efficient. The corresponding speedup is less than the theoretical optimum, which is visualized by a red line of slope \(1\).

There is no exact optimum and the best working point is open for discussion. However, it would be difficult to justify additional cores, if their contribution to speedup is only 50% efficient or even less.

If you have experience with python, you can use our python script to create the

same plots as above, but for your own data. It depends on

numpy, pandas, and matplotlib, so

make sure to prepare a corresponding python environment.

The script expects your .csv files to be called

strong.csv and weak.csv, and be placed in the

same directory.

So far, we kept the workload size fixed to \(800 \times 800\) pixels and \(128\) samples per pixel for the same scene with three snowman. The diminishing returns for adding more and more parallel processors leads to a famous observation. The speedup of a program through parallelization is limited by the execution time of the serial fraction that is not parallelizable. No application is 100% parallelizable, so adding an arbitrary amount of parallel processors can only affect the parallelizable section. In the best case, the execution time gets reduced to the serial fraction of the application.

An application is said to scale strongly, if adding more cores significantly reduces the execution time.

Amdahls Law1

The speedup of a program through parallelization is limited by the execution time of the serial fraction that is not parallelizable. For a given execution time \(T(N) = s + \frac{p}{N}\), with \(s\) the time for the serial fraction, and \(p\), the time for parallel fraction, speedup \(S\) is defined as \[S(N) = \frac{s+p}{s+\frac{p}{N}} = \frac{1}{s + \frac{p}{N}} \Rightarrow \lim_{N\rightarrow \infty} S(N) = \frac{1}{s}\]

Discussion: When should we stop adding CPU cores?

Discuss your previous results and decide on a good working point. How many cores are still usefully reducing the execution time.

What other factors could affect your decision, e.g. available hardware and corresponding waiting times.

If scaling is limited, why are there larger HPC systems? Weak scaling.

For a fixed problem size, we observed that adding more parallel processors can only help up to a certain point. But what if the project benefits from increasing the workload size? Does a higher resolution, more accuracy, or more statistics, etc., improve our insights and results? If that is the case, the perspective on the issue changes and adding more parallel processors can become more feasible as well. For our raytracer example, increasing the workload corresponds to more pixels, more samples per pixel, and/or a more complex scene.

Weak scaling refers to the scaling behavior of an application for a fixed workload per parallel processing unit, e.g. increasing the number of pixels by the same amount as the number of parallel processors \(N\).

Gustafsons Law2

A program scales on \(N\) parallel processors, if the problem size also scales with the number of processors. The speedup \(S\) becomes \[\text{S(N)} = \frac{s+pN}{s+p} = s+pN = N+s(1-N)\] with \(N\) processors, \(s\) the time for the serial fraction, and \(p\), the time for parallel fraction:

To scale the workload of the snowman raytracer, we can increase the number of calculated pixels with the same factor with which we increase the number of parallel processors. For one processor we have \(800 \times 800 = 640000\) pixel. That means for two processors we need a height and a width of \(\sqrt{2 \times 640000} = 1131.371 \approx 1131\). And similarly increasing the number of pixels for \(--ntasks=4\) and so on.

The job script could look like this:

BASH

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=3800MB

module load 2025 GCC/13.2.0 OpenMPI/4.1.6 buildenv/default Boost/1.83.0 CMake/3.27.6 libpng/1.6.40

# Create associative array

declare -A pixel

pixel[1]="800"

pixel[2]="1131"

pixel[4]="1600"

pixel[8]="2263"

pixel[16]="3200"

pixel[32]="4526"

pixel[64]="6400"

time mpirun -- ./build/raytracer -width=${pixel[${SLURM_NTASKS}]} -height=${pixel[${SLURM_NTASKS}]} -spp=128 -threads=1 -png "$(date +%Y-%m-%d_%H%M%S).png"To scale the workload of the snowman raytracer, we can multiply the

number of parallel MPI processes, ${SLURM_NTASKS}, with the

samples per pixel (starting from -spp=128). For a single

process, the whole \(800 \times 800\)

pixel picture is calculated in a single MPI process with 128 per pixel.

Running with two MPI processes, both have to calculate half the number

of pixels, but twice the amount of samples per pixel.

BASH

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=500MB

module load 2025 GCC/13.2.0 OpenMPI/4.1.6 buildenv/default Boost/1.83.0 CMake/3.27.6 libpng/1.6.40

SPP="$[${SLURM_NTASKS}*128]"

time mpirun -- ./build/raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp=${SPP} -threads=1 -png "$(date +%Y-%m-%d_%H%M%S).png"

In direct comparison, and zooming in really close, you can see more noise in the first image, e.g. in the shadows. One could argue that we passed the point of diminishing returns, though. Is a \(64\times\) increase in computational cost worth the observed quality improvement? For the samples per pixel, we seem to not benefit much from weak scaling. Larger resolutions, by increasing the number of pixels, is the more useful dimension to increase in this case.

Increasing the resolution may be worth the effort, if we have a use for a larger, more detailed picture. In practice, there is a cutoff, beyond which no reasonable improvement is to be expected. This is a question about accuracy, error margins, and overall quality, which can only be answered in the specific context of each research project. If there is no real improvement by increasing the workload, running a weakly scaling application is really just wasting valuable computational time and energy.

If we increase the workload at the rate as our number of parallel processes (\(N\)) our speedup is defined as \[S_{\text{weak}}(N) = \frac{T(1)}{T(N)} \times N\] since we do \(N\) times more work with \(N\) processors, compared to our reference \(T(N=1)\). Efficiency is still defined as \[\eta_{\text{weak}}(N) = \frac{S_{\text{weak}}(N)}{N} = \frac{T(1)}{T(N)}\]

Exercise: Weak scaling

Repeat the previous scaling study and increase the number of pixels accordingly to study the raytracers weak scaling behavior.

- Run with 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 MPI processes on single node

- Take

timemeasurements and consider running with--exclusiveto ensure more reliable results. - Create a

.csvfile and run the plotting script

ntasks,pixel,time,speedup,efficiency

1,800,123.162

2,1131,122.562

4,1600,124.522

8,2263,125.606

...How well does the application scale with an increasing workload size?

Do you see a qualitative difference in the resulting .png

files and is the increased sample-per-pixel size worth the computational

costs?

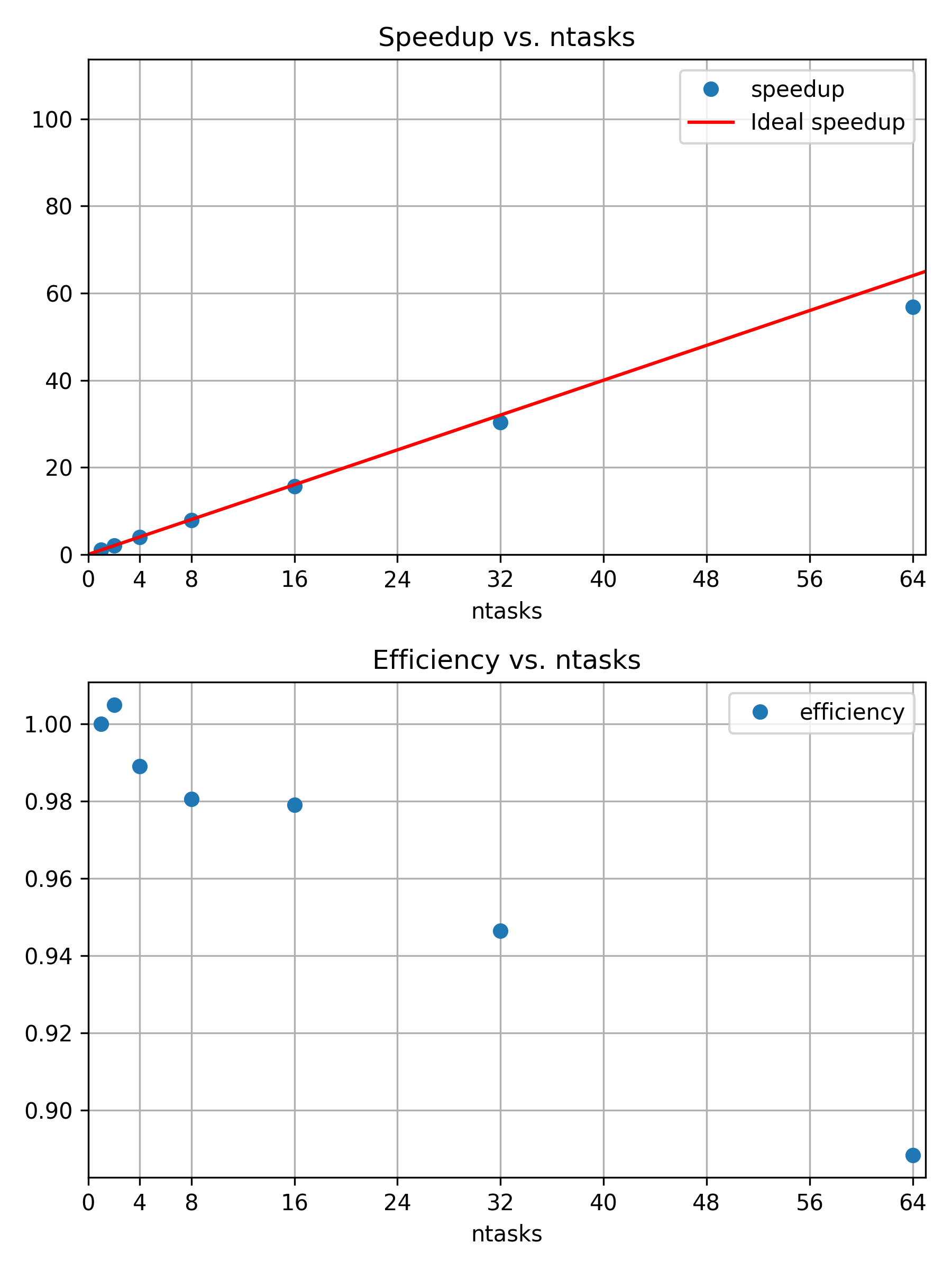

ntasks,pixel,time,speedup,efficiency

1,800,123.162

2,1131,122.562

4,1600,124.522

8,2263,125.606

16,3200,125.803

32,4526,130.137

64,6400,138.636The scaling behavior is reaching an asymptotic limit, where each additional processor is contributing with the same efficiency to the increased workload.

Weakly scaling jobs can make efficient use of a huge amount of resources.

The most important question is, if an increased workload is producing useful results. Here, we have the rendered picture of three snowmen in 800x800 with 128 samples per pixel and three snowmen in 6400x6400 with 128 samples per pixel. The second image has a much higher resolution. However, going way beyond \(6400 \times 6400\) pixels is probably not very meaningful, unless you are trying to print the worlds largest ad boards or similar.

Summary

In this episode, we have seen that we can study the scaling behavior of our application with respect to different metrics, while varying its configuration. Most commonly, we study the execution time of an application with an increasing number of parallel processors. In such a scaling study, we collect comparable walltime measurements for an increasing number of Slurm tasks of a parallelizable and representative job. If a good working point is found, larger scale “production” jobs can be submitted to the HPC system.

If the application has good strong scaling behavior, adding more cores leads to an effective improvement in execution time. We observe diminishing returns of adding more cores to a fixed-size problem, so there is a (subjective) optimal number of parallel processors for a given application configuration. (Amdahls Law)

If increasing the workload size leads to better results, maybe because of improved accuracy and quality, we can study the weak scaling behavior and increase the workload size by the same factor of increasing parallel processors.

A good working point depends on the availability of resources, specifics of the underlying hardware, the particular application, and a particular configuration for the application. For that reason, scaling studies are a common requirement for formal compute time applications to prove an efficient execution of a given application.

We can study the impact of any parameter on metrics like, for example, walltime, CPU utilization, FLOPS, memory utilization, communication, output size on disk, and so on.

If you find yourself repeating similar measurements over and over again, you may be interested in an automation approach. This can be done by creating reproducible HPC workflows using JUBE, among other things.

Up to now, we were still working with basic metrics like the wall-clock time. In the next episode, we start with more in-depth measurements of many other aspects of our job and application.

- Jobs behave differently with increasing parallel resources and fixed or scaling workloads

- Scaling studies can help to quantitatively grasp this changing behavior

- Good working points are defined by configurations where more cores still provide sufficient speedup or improve quality through increasing workloads

- Amdahl’s law: speedup is limited by the serial fraction of a program

- Gustafson’s law: more resources for parallel processing still help, if larger workloads can meaningfully contribute to project results

G. M. Amdahl, ‘Validity of the single processor approach to achieving large scale computing capabilities’, in Proceedings of the April 18-20, 1967, spring joint computer conference, in AFIPS ’67 (Spring). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Apr. 1967, pp. 483–485. doi: 10.1145/1465482.1465560.↩︎

J. L. Gustafson, ‘Reevaluating Amdahl’s law’, Commun. ACM, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 532–533, May 1988, doi: 10.1145/42411.42415.↩︎