Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What exactly is job efficiency in the computing world?

- Why would I care about job efficiency and what are potential pitfalls?

- How can I start measuring how my program performs?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to …

- Use timing commands provided by

timeanddate. - Understand the benefits of efficient jobs in terms of runtime and numerical accuracy.

- Have developed some awareness about the overall high energy consumption of HPC.

Background

Job efficiency, as defined by Oxford’s English Dictionaries, is the ratio of the useful work performed by a machine […] to the total energy expended or heat taken in. In a high-performance-computing (HPC) context, the useful work is the entirety of all calculations to be performed by our (heat-generating) computers. Doing this efficiently thus translates to maximizing the calculations completed in some limited time span while minimizing the heat output. In more extreme words, we want to avoid running big computers for nothing but hot air.

One may object that a single user’s job may hardly have an effect on an HPC system’s power usage since such systems are in power-on state 24/7 anyway. The same may be argued about air travel. The plane will take off anyway, whether I board the plane or not. However, we indeed have some leverage in contributing to efficiency, defined by fuel consumption in air travel: traveling lightly, i.e., avoiding excessive baggage will improve the airplane’s ratio \(\frac{useful\;work}{total\;energy\;expended}\). So let’s get back to the ground and look at some inefficiencies in computing jobs, while we will continue to use the air-travel analogy.

time to sleep

Let’s look at the commandsleep

This command triggers a “computer nap”. It actually delays whatever

would come next for the specified time, here 2 seconds. You can verify

that nap time using a stopwatch, the latter given by

thetimecommand:

which will report something like

real 0m2.002s

user 0m0.001s

sys 0m0.000sThe time command shall be our first

performance-measuring tool. timehas become a bit of a

hello-world equivalent in HPC contexts. This command gives you

a breakdown of how your program uses CPU (Central Processing Unit) and

wall-clock time. The standard output of time reports three

fields, real, user and sys:

| Time | Meaning |

| real | Wall-clock time = total runtime as seen on a stopwatch |

| user | Time spent in user-mode: actual computations like math, loops, logic |

| sys | Time spent in OS’s kernel-mode (system calls): I/O = reading/writing files, handling memory, talking to other devices |

The abovesleepcommand abstains from any kind of math,

I/O, or other work that would show up in user or sys

time, hence these entries show (almost) zero.

Thetimecommand is both a keyword directly built into the

Bash shell as well as an executable file, usually residing

under/usr/bin/time. While very similar, they are not

exactly the same. Shell/Bash keywords take precedence, so preceding a

command withtimeinvokes the shell keyword. Therefore, if

you want to force the usage of/usr/bin/time, you would

do

BASH

# Explicitly calling the `time` binary

$ /usr/bin/time sleep 2

0.00user 0.00system 0:02.00elapsed 0%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 2176maxresident)k

0inputs+0outputs (0major+90minor)pagefaults 0swaps

# Compare the output to the Bash built-in:

$ time sleep 2

real 0m2,003s

user 0m0,001s

sys 0m0,003s

# Yet another output of `time` in zsh, an alternative shell implementation to bash

$ time sleep 2

sleep 2 0,00s user 0,00s system 0% cpu 2,003 totalNotice the different output formatting. All tools provide similar insight, but the formatting and exact information may differ. So, if you saw something that looks different from the bash built-in command, this may be why!

Further note, that shell keyword documentation is invoked

viahelp <KEYWORD>, for example

help time, while most executables have manual pages,

e.g.,man time. At last, you can prefix the shell keyword

with a backslash in order to stop Bash from evaluating it,

so\time sleep 2will revert

to/usr/bin/time.

Time for a date

Thedatecommand, as its manpage (man date)

says, prints or sets the system date and time. In fact, this gives us a

super accurate stopwatch when used like this:

reports a point in time as a number of seconds elapsed since a fixed reference point.

A referenced time point is also referred to as Epoch time, where,

according to the manpage ofdate, the (default) reference

point is the beginning of the year 1970, given as “1970-01-01 00:00

UTC”.

While%sinvokes output of a referenced time, the

additional specifier%Nenforces an accuracy down to

nanoseconds. Give it a try and you will see a large number (of seconds)

followed by 9 digits after the decimal point.

An accurate stopwatch: date

You can use the constructdate +%s.%Non the command line

or in a Bash script to save start and end time points as a variable:

This gives you a stopwatch by setting a start time, running some

command(s), and then storing the end time after

command(s) into a second variable. Differencing the two

times produces the elapsed time. Give this a try with

thesleepcommand in between.

Part 1: Example for an inefficient job

After warming up with some timing methods, let’s analyze the

efficiency of a small script that makes our computer sweat a bit more

than thesleepcommand. Have a look at the following Bash

shell 7-liner.

BASH

#!/bin/bash

sum=0

for i in $(seq 1 1000); do

val=`echo "e(2 * l(${i}))" | bc -l`

sum=$(echo "$sum + $val" | bc -l)

done

echo Sum=$sumCopy-paste this to a file, saysum.bash, and make it

executable via

The main part of this shell script consists of

aforstatement which is calculating the sum of all squares

\(i^2\) for 1000 iterations; note

thatseq 1 1000creates the number sequence (\(i=1,2,3,...,1000\)). Inside the

forloop thebccalculator tool is employed. The

first statement inside the loop (val=...) prints the

expression e(2 * l(${i})), which is bc-talk

for the expression \(i^2\) because of

the relation \(i^x=e^{x\cdot \ln(i)}\),

for example \(e^{2\cdot\ln(3)}=3^2\),

where ln is the natural logarithm. The second statement inside the loop

(sum=...) accumulates the expressions

val=\(i^2\)

intosum, so the output of the finalecholine is

the total, \(\sum_{i=1}^{1000}i^2\).

Identify the inefficient pieces

In the above Bash script, theforloop invokes the

bccalculator twice during every loop iteration. Compared to

another method to be investigated below, this method is rather slow. Any

idea why that is the case?

Each statementecho … | bc -lspawns a

newbcprocess via a subshell.

The statementecho … | bc -lspawns a

newbcprocess via a subshell. Here, each loop iteration

invokes two of those. Each subshell is essentially a separate process

and involves a certain startup cost, parsing overhead, and OS-internal

inter‑process communication. Such overhead will account for most of the

total runtime ofsum.bash.

The overhead in this shell script is dominated by process creation

and context switching, that is, calling thebctool so many

times. Going back to our air-travel analogy, the summation of 1000

numbers shall be equivalent to having a total of 1000 passengers board a

large plane. When total boarding time counts, an inefficient boarding

procedure would involve every passenger loading two carryon pieces. Many

of you may have experienced, how stuffing an excessive number of baggage

pieces into the overhead compartments can slow things down in the

plane’s aisles, similar to the overhead due to the 2000 (two for each

loop iteration)bcsub-processes that hinder the data stream

inside the CPU’s “aisles”.

Let’s pull out our stopwatches

Using eithertimeordate, can you get a

runtime measurement forsum.bash?

You can precede any command withtime. If you want to

usedate, remember thatnow=$(date +%s.%N)lets

you store the current time point and&&lets you join

commands together.

A straightforward way is

Alternatively,dateand&&can be

combined to a wrapper in order to

timesum.bashexternally,

Another option is to placedateinside the

scriptsum.bash,

Speeding things up

A remedy to the inefficiencies we found inside

theforloop ofsum.bashis to avoid the spawning

of many sub-processes that are caused by repetitively

callingbc. In other words, ideally, the many sub-processes

conflate into one. In terms of the airplane analogy, we want people to

store all their carryon pieces in a big container, where its subsequent

loading onto the plane is a single process, as opposed to every

passenger running a proprietary sub-process. Collapsing things into one

sub-processes can be achieved by replacing the external loop by

abc-internal one:

In this method, to be called the one-liner, the loop, arithmetic, and accumulation are free of the overhead. This example shall be a placeholder for a common scenario, where potentially large efficiency gains can be achieved by replacing inefficient math implementations by numerically optimized software libraries.

Evaluate the runtime improvement

Compare the runtimes of the summation

scriptsum.bashversus the one-liner.

The Bash keywordtimeis sufficient to see the runtime

difference.

While it depends a bit on the employed hardware, one will notice that

the one-liner runs roughly 1000 times faster thansum.bash.

Of course, one could live with this inefficiency when it is just needed

once in a while and the script’s overall runtime amounts to just a few

seconds. However, imagine some large-scale computing job that is

supposed to finish within an hour on a supercomputer for which one has

to pay a usage fee on a per-hour basis. If implemented poorly, an

already small overhead increase, say by a factor of 2, would render this

computing job expensive, both in terms of time and money.

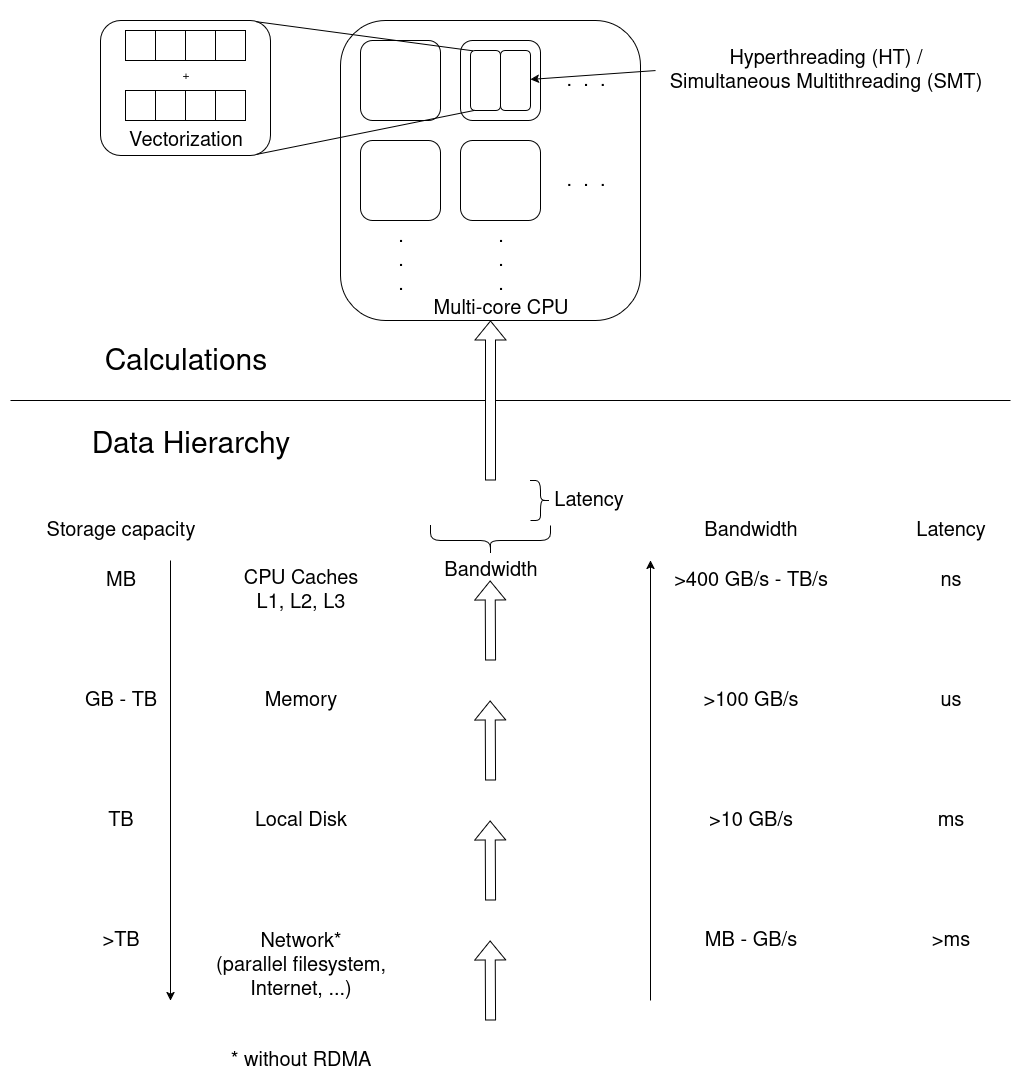

The above runtime comparisons merely look at calculation speed, which depends on CPU processing speed. Such a task is thus called CPU-bound. On the other hand, the performance of a memory-bound process is limited by the speed of memory access. This happens when the CPU spends most of its time waiting for data to be fetched from memory (RAM), cache, or storage, causing its execution pipeline to stall. Optimization of memory-bound tasks addresses performance bottlenecks due to data transfer speeds rather than calculation speeds. Finally, when data transfer involves a high percentage of disk or network access, disk/networking speed becomes a limiting factor, rendering a process I/O-bound.

To be precise: Numerical efficiency

Inefficient computing is not only limited to being unnecessarily slow. It can also entail the scenario where an excessive accuracy can lead to unnecessary runtime increases. Without going into details, let’s just keep in mind that in computing, accuracy depends on the precision of the numbers that are being processed by the CPU. Precision essentially governs how many digits after the decimal point are accounted for in mathematical operations. The higher the precision, the fewer calculations can be processed within a fixed time. On the other hand, within that same time, the CPU can crank through more low-precision numbers; however, an insufficient precision can render lengthy calculations useless. The optimal degree of precision, in terms of computing efficiency, is application dependent.

Compare numerical results

Our summation implementation viasum.bashexemplifies the

case of an inaccurate calculation. When running the two summation

methods in the previous challenge, have a look at the actual summation

results. Which of the two end results do you think is more accurate and

why? Is the erroneous result smaller or larger and why?

Think of another airplane example. Which scenario is more prone to things getting lost or forgotten? 1) Passengers bring and take their own baggage pieces to the cabin, or 2) Baggage pieces are stored and retrieved collectively.

The methodsum.bash, using the

externalforloop, and the one-liner return the final sums,

respectively,

103075329 # bc, external loop (sum.bash)

333833500 # bc, internal loop (one-liner)where the first result may vary on your machine. The

methodsum.bashis affected by the setting of the

bc-internal parameterscalewhich defines how

some operations, here the exponential function e(…) and

logarithm ln(…) use digits after the decimal point. The

default value ofscaleis 0, which basically leads to

truncations after the decimal point, so rounding errors accumulate at

every loop iteration. Hence, the final sum drifts downward (by a lot)

compared to the second (true) value. Of course,scalecan be

increased. The manpage ofbcactually says that it is “an

arbitrary precision calculator language”.

Part 2: About HPC power consumption

The HP (high performace) in HPC refers to the fact that the employed computer hardware is able to do a lot of multitasking, also called parallel computing. Parallel programming essentially exploits the CPU’s multitasking ability. Therefore, a lot of HPC-efficiency aspects revolve around keeping everyone in a CPU’s multitasking team equally busy. We will look at some of those aspects during the course of later episodes.

The more the merrier: CPU/GPU cores

Common parallel-computing jobs employ multiple cores of a CPU, or even multiple CPUs, simultaneously. A core is a processing unit within a CPU that independently executes instructions. These days (as of 2025), typical CPUs are quad-core (4 cores), octa-core (8 cores), and so on. High-end gaming CPUs often have 16+ cores, HPC cluster nodes feature multiple CPUs, oftentimes with 64+ cores each; and all these numbers keep going up.

Nowadays, almost all HPC centers are also equipped with GPU (Graphics

Processing Unit) hardware. Such hardware is optimal for jobs where

many cores is more important than fewer powerful cores.

The number of GPU cores varies greatly depending on the model, ranging

from a few hundred in low-end GPU cards to over 16,000 in high-end

ones.

Measuring parallel runtime: core hours

Owing to the inherent parallelism in the HPC world, people came up with some measure which takes the granularity into account when allocating not only runtime but also the number of requested cores. The unit core hour (core-h) represents the usage of one CPU core for one hour and scales with core count. For example, assume you have a monthly allocation of 500 core-h, with a fee incurred when exceeding that quota. So with 500 core-h, you could run a one-hour parallel job utilizing 500 CPU cores for free. Or, in the other extreme, if your program does not or cannot multitask, you could run a single-core job for 500 hours, provided you won’t forget at the end what this job was about.

So far, the focus has been on core number and hours for HPC resource allocation. Keep in mind, however, that the HPC resource portfolio involves other hardware components as well:

- Memory: There are (whether parallel or not) jobs, that request a large amount of memory (RAM). For example, some mathematical solution methods for large equation systems do not allow the compartmentalization of the total required memory across CPU cores, that is, many-core processes need to know each other’s memory chunks. HPC centers usually have large-memory nodes assigned for such applications.

- Storage: Other applications process huge amounts of data, think of genomics or climate modelling, which can involve terabytes or even petabytes of data to be stored and analyzed.

A typical HPC computing job

Like in the automotive world, high performance means high power, which in turn involves a high energy demand. Let’s consider a typical parallel scientific-computing job to be run in some HPC center. Our example job shall be deemed too large for one CPU, so it employs multiple CPUs, which in turn are distributed across nodes. Node power usage is measured in W=Watt, which is the SI unit of power and corresponds to the rate of consumption of energy in an electric circuit. One compute node with a 64-core CPU can consume between 300 W in idle state, and 900 W (maximum load) for air-cooled systems, whereas this range is roughly 250-850 W for the slightly more efficient liquid-cooled systems. For comparison, an average coffee maker consumes between 800 W (drip coffee maker) and 1500 W (espresso machine). Our computing job shall then use these resources:

- 12 nodes are crunching numbers in parallel

- 64 cores/node (e.g., Intel® Xeon® 6774P, or AMD® EPYC® 9534)

- 12 hours of full load (realistic for many scientific simulations)

- Power per node: (idle vs. full load):

- Idle: ~300 W

- Full load: ~900 W

- Extra power per node: 600 W

- Total extra power: 12 nodes × 600 W × 12 hours = 86,400 Wh = 86.4 kWh

How many core hours does this job involve?

HPC centers have different job queues for different kinds of computing jobs. For example, a queue named big-jobs may be reserved for jobs exceeding a total of 1024 parallel processes = tasks. Another queue named big-mem may accomodate tasks with high memory demands by giving access to high-memory nodes (e.g., 512 GB, 1 TB, or more RAM per compute node).

Let’s assume, you have three job queues available, all with identical memory layout:

-

small-jobs: Total task count of up to 511. -

medium-jobs: Total task count 512-1023. -

big-jobs: Total task count of 1024 or more.

When submitting the above computing job, in which queue would it end up? And, if there would be a charge of 1 Cent per core-h, what is the total cost in € (1€ = 100 Cents)?

The total number of tasks results from the product cores-per-node \(\times\) nodes. Total core hours is the task count multiplied by the job’s requested time in hours.

The total number of tasks is cores-per-node \(\times\) nodes = \(64\times 12 = 768\), which would put the

job into themedium-jobsqueue. The HPC center would bill us

for \(64\times 12\times 12 = 9216\)

core hours, hence €92.16.

What are Watt hours?

The unit Wh (Watt-hours) measures energy, so 86,400 Wh is the energy that a 86,400 W (or 86.4 kW, k=kilo) powerful machine consumes in one hour. Back to coffee, brewing one cup needs 50-100 Wh, depending on preparation time and method. So, running your 12-node HPC job for 12 hours is equivalent to brewing between 864 and 1,728 cups of coffee. For those of us who don’t drink coffee, assuming 100% conversion efficiency from our compute job’s heat to mechanical energy, which is unrealistic, we could lift an average African elephant (~6 tons) about 5,285 meters straight up, not quite to the top but in sight of Mount Kilimanjaro’s (5,895 m) summit.

Note that the focus is on extra power, that is, beyond the CPU’s idle state. Attributing our job’s extra power only to CPU usage underestimates its footprint. In practice, the actual delta from idle to full load will vary based on the load posed on other hardware components. Therefore, it is interesting to shed some light onto those other hardware components that start gearing up after hitting that Enter key which submits the above kind of HPC job.

-

CPUs consume power through two main processes:

- Dynamic power consumption: It is caused by the constant switching of transistors and is influenced by the CPU’s clock frequency and voltage.

- Static power consumption: It is caused by small leakage currents even when the CPU is idle. This is a function of the total number of transistors.

Both processes convert electrical energy into heat, which makes CPU cooling so important.

Memory (DRAM) consumes power primarily through its refresh cycles. These are required to counteract the charge leakage in the data-storing capacitors. Periodic refreshing is necessary to maintain data integrity, which is the main reason why DRAM draws power even when idle. Other power consumption factors include the static power drawn by the memory’s circuitry and the active power used during read/write operations.

Network interface cards (NICs) consume power by converting digital data into electrical signals for transmission and reception. Power draw increases with data throughput, physical-media complexity, like fiber optics, and also depends on the specific interconnect technology used.

Storage components: Hard drives (HDDs) require constant energy due to moving mechanical parts, like the disc-spinning motors. SSDs store data electronically via flash memory chips and are thus more power-efficient, especially when idle. However, when performing heavy read/write tasks, SSD power consumption can also be significant, though they complete these tasks faster than HDDs and return to their idle state sooner.

-

Cooling is one of the biggest contributors to total energy use in HPC:

- Idle: Cooling uses ~10–20% of total system power.

- Max load: Cooling can consume ~50–70% of total power (depends on liquid- or air-cooled systems).

Cooling is essential because all electrical circuits generate heat during operation. Under heavy computational loads, insufficiently cooled CPUs and GPUs exceed their safe temperature limits.

These considerations hopefully highlight why there is benefit in identifying potential efficiency bottlenecks before submitting an energy-intense HPC job. If all passengers care about efficient job design, i.e., the total baggage load, more can simultaneously jump onto the HPC plane.

- Using a stopwatch like

timegives you a first tool to log actual versus expected runtimes; it is also useful for carrying out runtime comparisons. - Which hardware piece (CPU, memory/RAM, disk, network, etc.) poses a limiting factor, depends on the nature of a particular application.

- Large-scale computing is power hungry, so we want to use the energy wisely. As shown in the next episodes, you have more power than it may be expected over controlling job efficiency and thus overall energy footprint.

- Computing job efficiency goes beyond individual gain in runtime as shared resources are used more effectively, that is, the ratio \(\frac{useful\;work}{total\;energy\;expended}\sim\frac{number\;of\;users}{total\;energy\;expended}\) improves.

So what’s next?

The following episodes will put a number of these introductory thoughts into concrete action by looking at efficiency aspects around a compute-intense graphical program. While it is not directly an action-loaded video game, it does contain essential pieces thereof, because it uses the technique of ray tracing.

Ray tracing is a technique that simulates how light travels in a 3D scene to create realistic images. It simulates the behaviour of light in terms of optical effects like reflection, refraction, shadows, absorption, etc. The underlying calculations involve real-world physics, which makes them computationally expensive - a perfect HPC case.

Here is a basic run script:

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --tasks-per-node=4

# Put in the same "module load ..." command when building the raytracer program

time mpirun -np 4 raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp=128Check thetimeoutput at the end of the job’s output file

(named something like slurm-<NUMBER>.out). You will

notice that user time is by a certain factor larger than

real time.

Why is the user timer larger than the real

time, and what does it mean?

Any guess which number in the mpirunline corresponds

roughly to that factor?

Content from Resource Requirements

Last updated on 2025-12-15 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How many resources should I request initially?

- What scheduler options exist to request resources?

- How do I know if they are used well?

- How large is my HPC cluster?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to …

- Identify the size of their jobs in relation to the HPC system.

- Request a good amount of resources from the scheduler.

- Change the parameters to see how the execution time changes.

When you run a program on your local workstation or laptop, you typically don’t plan out the usage of computing resources like memory or core-hours. Your applications simply take as much as they need and if your computer runs out of resources, you can just a few. However, unless you are very rich, you probably don’t have a dedicated HPC cluster just to yourself and instead you have to share one with your colleagues. In such a scenario greedily consuming as many resources as possible is very impolite, so we need to restrain ourselves and carefully allocate just as many resources as needed. These resource constraints are then enforced by the cluster’s scheduling system so that you cannot accidentally use more resources than you think.

Getting a feel for the size of your cluster

To start with your resource planning, it is always a good idea to first get a feeling for the size of the cluster available to you. For example, if your cluster has tens of thousands of CPU cores and you use only 10 of them, you are far away from what would be considered excessive usage of resources. However, if your calculation utilizes GPUs and your cluster has only a handful of them, you should really make sure to use only the minimum amount necessary to get your work done.

Let’s start by getting an overview of the partitions of your cluster:

Here is a (simplified) example output for the command above:

PARTITION NODES CPUS MEMORY GRES TIMELIMIT

normal 223 36 95000+ (null) 1-00:00:00

long 90 36 192000 (null) 7-00:00:00

express 6 36 95000+ (null) 2:00:00

zen4 46 192 763758+ (null) 2-00:00:00

gpuexpress 1 32 240000 gpu:rtx2080:7 12:00:00

gpu4090 8 32 360448 gpu:rtx4090:6 7-00:00:00

gpuh200 4 128 1547843 gpu:h200:8 7-00:00:00In the output, we see the name of each partition, the number of nodes in this partition, the number of CPU cores per node, the amount of memory per node (in Megabytes (or Mebibytes?)), the number of generic resources (typically GPUs) per node and finally the maximum amount of time any job is allowed to take.

Compare the resources available in the different partitions of your local cluster. Can you draw conclusions on what the purpose of each partition is based on the resources it contains?

For our example output above we can make some educated guesses on what the partitions are supposed to be used for:

- The

normalpartition has a (relatively) small amount of memory and limits jobs to at most one day, but has by far the most nodes. This partition is probably designed for small- to medium-sized jobs. Since there are noGRESin this partition, only CPU computations can be performed here. Also, as the number of cores per node is (relatively) small, this partition only allowd multithreading up to 36 threads and requires MPI for a higher degree of parallelism. - The

longpartition has double the memory compared to thenormalpartition, but less than half the number of nodes. It also allows for much longer running jobs. This partition is likely intended for jobs that are too big for thenormalpartition. -

expressis a very small partition with a similar configuration tonormal, but a very short time limit of only 2 hours. The purpose of this partition is likely testing and very short running jobs like software compilation. - Unlike the former partitions,

zen4has a lot more cores and memory per node. The intent of this partition is probably to run jobs using large-scale multithreading. The name of the partitions implies a certain CPU generation (AMD Zen 4), which appears to be newer than the CPU model used in thenormal,longandexpresspartitions (typically core counts increase in newer CPU generations). -

gpuexpressis the first partition that features GPU resources. However, with only a single node and a maximum job duration of 12 hours, this partition seems to be intended again for testing purposes rather than large-scale computations. This also matches the relatively old GPU model. - In contrast,

gpu4090has more nodes and a much longer walltime of seven days and is thus suitable for actual HPC workloads. Given the low number of CPU cores, this partition is intended for GPU workloads only. More details can be gleamed from the GPU model used in this partition (RTX 4090). This GPU type is typically used for Workloads using single-precision floating point calculations. - Finally, the

gpuh200partition combines a large number of very powerful H200 GPUs with a high core count and a very large amount of memory. This partition seems to be intended for the heaviest workloads that can make use of both CPU and GPU resources. The drawback is the low number of nodes in this partition.

To get a point of reference, you can also compare the total number of cores in the entire cluster to the number of CPU cores on the login node or on your local machine.

BASH

lscpu | grep "CPU(s):"

# If lscpu is not available on your machine, you can also use this command

cat /proc/cpuinfo | grep "core id" | wc -lAs you can see, your cluster likely has multiple orders of magnitude more cores in total than the login node or your local machine. To see the amount of memory on the machine you are logged into you can use

Again, the total memory of the cluster is going to be much, much larger than the memory of any individual machine.

All of these cores and all of that memory are shared between you and all the other users of your cluster. To get a feeling for the amount of resources per user, let’s try to get an estimate for how many users there are by counting the number of home directories.

On some clusters, home directories are not placed directly in

/home, but are split up into subdirectories first (e.g., by

first letter of the username like /home/s/someuser). In

this case, you have to use -maxdepth 2 -mindepth 2 to count

the contents of these subdirectories. If your cluster does not use

/home for the users’ home directories, you might have to

use a different path (check dirname "$HOME" for a clue).

Also, this command only gives an upper limit to the number of real

cluster users as there might be home directories for service users as

well.

By dividing the total number of cores / the total memory by the amount of users, you get an estimate of how many resources each user has available in a perfectly fair world.

Does this mean you can never use more than this amount of resources?

Now that you have an idea of how big your cluster is, you can start to make informed decisions on how many resources are reasonable to ask for.

Challenge

sinfo can show a lot more information on the nodes and

partitions of your cluster. Check out the documentation

and experiment with additional output options. Try to find a single

command that will shows for each command the number of allocated and

idle nodes and CPU cores.

BASH

$ sinfo -O Partition,CPUsState,NodeAIOT

PARTITION CPUS(A/I/O/T) NODES(A/I/O/T)

normal* 6336/720/972/8028 196/0/27/223

long 2205/351/684/3240 71/0/19/90

express 44/172/0/216 3/3/0/6

zen4 7532/1108/192/8832 44/1/1/46

gpuexpress 0/32/0/32 0/1/0/1

gpu4090 177/35/44/256 7/0/1/8

gpuh200 90/166/256/512 2/0/2/4Sizing your jobs

The resources required by your jobs primarily depend on the application you want to run and are thus very specific to your particular HPC use case. While it is tempting to just wildly overestimate the resource requirements of your application to make sure it cannot possibly run out, this is not a good strategy. Not only would you have to face the wrath of your cluster administrators (and the other users!) for being inefficient, but you would also be punished by the scheduler itself: In most cluster configurations, your scheduling priority decreases faster if you request more resources and larger jobs often need to wait longer until a suitable slot becomes free. Thus, if you want to get your calculations done faster, you should request just enough resources for your application to work.

Finding this amount of resources is often a matter of trial and error

as many applications do not have precisely predictable resource

requirements. Let’s try this for our snowman renderer. Put the following

in a file named snowman.job:

BASH

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --partition=<put your partition here>

#SBATCH --ntasks=4

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task=1

#SBATCH --mem=1G

#SBATCH --time=00:01:00

#SBATCH --output=snowman-stdout.log

#SBATCH --job-name=snowman

# Always a good idea to purge modules first to start with a clean module environment

module purge

# <put the module load commands for your cluster here>

# Start the raytracer

mpirun -n 4 ./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=1 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.pngThe #SBATCH directives assign our job the following

resources (line-by-line):

- 1 node…

- … from the partition

<put your partition here> - 4 MPI tasks…

- … each of which uses one CPU core (so 4 cores in total)

- 1 GB of memory

- A timelimit of 1 minute

The last two #SBATCH directives specifiy that we want

the output of our job to be captures in the file

snowman-stdout.log and that the job should appear under the

name snowman.

The --mem directive is somewhat unfortunately named as

it does not define the total amount of memory of your job, but the total

amount of memory per node. Here, this distinction does not

matter as we only use one node, but you should keep in mind that

changing the number of nodes often implies that you need to adapt the

--mem value as well. Alternatively, you can also use the

--mem-per-cpu directive such that the memory allocation

automatically scales with the number of cores. However, even in this

case you need to verify that your memory consumption actually scales

linearly with the number of cores for your application!

To test if our estimate works, you have to submit the job to the scheduler:

This command will also print the ID of the job, so we can observe what is happening with it. Wait a bit and have a look at how your job is doing:

After a while, you will see that the status of your job is given as

TIMEOUT.

You might wonder what the -X flag does in the the

sacct call above. This option instructs Slurm to not output

information on the “job steps” associated with your job. Since we don’t

care about these right now, we set this flag to make the output more

concise.

Check the file snowman-stdout.log as well. Near the

bottom you will see a line like this:

slurmstepd: error: *** JOB 1234567 ON somenode CANCELLED AT 2025-04-01T13:37:00 DUE TO TIME LIMIT ***Evidently our job was aborted because it did not finish within the time limit of one minute that we set above. Let’s try giving our job a time limit of 10 minutes instead.

This time the job should succeed and show a status of “COMPLETED” in

sacct. We can check the resources actually needed by our

job with the help of seff:

The output of seff contains many useful bits of

information for sizing our job. In particular, let’s look at these

lines:

[...]

CPU Utilized: 00:21:34

CPU Efficiency: 98.93% of 00:21:48 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:05:27

Memory Utilized: 367.28 MB

Memory Efficiency: 35.87% of 1.00 GBThe exact numbers here depend a lot on the hardware and software of your local cluster.

The Job Wall-clock time is the time our job took. As we

can see, our job takes much longer than one minute to complete which is

why our first attempt with a time limit of one minute has failed.

The CPU Utilized line shows us how much CPU time our job

has used. This is calculated by determining the busy time for each core

and then summing these times for all cores. In an ideal world, the CPU

cores should be busy for the entire time of our job, so the CPU time

should be equal to the time the job took times the number of CPU cores.

The ratio between the real CPU time and the ideal CPU time is shown in

the CPU Efficiency line.

Finally, Memory utilized line shows the peak memory

consumption that your job had at any point during its runtime, while

Memory Efficiency is the ratio between this peak value and

the requested amount of memory for the allocation. As we will see later,

this value has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Starting from the set of parameters that successfully run our

program, we can now try to reduce the amout of requested resources. As

is good scientific practice, we should only vary one parameter at a time

and observe the result. Let’s start by reducing the time limit. There is

often a bit of jitter in the time needed to run a job since not all

nodes are perfectly identical, so you should add a safety margin of 10

to 20 percent (completely arbitrary choice of

numbers here; does everyone agree on the order of magnitude?)

According to the time reported by seff, seven minutes

should therefore be a good time limit. If your cluster is faster, you

might reduce this even further.

As you can see, your job will still complete successfully.

Next, we can optimize our memory allocation. According to SLURM, we used 367.28 MB of memory in our last run, so let’s set the memory limit to 500 MB.

After submitting the job with the lowered memory allocation

everything seems fine for a while. But then, right at the end of the

computation, our job will crash. Checking the job status with

sacct will reveal that the job status is

OUT_OF_MEMORY meaning that our job exceeded its memory

limit and was terminated by the scheduler.

This behavior seems contradictory at first: SLURM reported previously that our job only used around 367 MB of memory at most, which is well below the 500 MB limit we set. The explanation for this discrepancy lies in the fact that SLURM measures the peak memory consumption of jobs by polling, i.e., by periodically sampling how much memory the job currently uses. Unfortunately, if the program has spikes in memory consumption that are small enough to fit between two samples, SLURM will miss them and report an incorrect peak memory value. Spikes in memory usage are quite common, for example if your application uses short-lived subprocesses. Most annoyingly, many programs allocate a large chunk of memory right at the end of the computation to write out the results. In the case of the snowman raytracer, we encode the raw pixel data into a PNG at the end, which means we temporarily keep both the raw image and the PNG data in memory.

SLURM determines memory consuption by polling, i.e.,

periodically checking on the memory consumption of your job. If you job

has a memory allocation profile with short spikes in memory usage, the

value reported by seff can be incorrect. In particular, if

the job gets cancelled due to memory exhaustion, you should not rely on

the value reported by seff as it is likely significantly

too low.

So how big is the peak memory consumption of our process really? Luckily, the Linux kernel keeps track of this for us, if SLURM is configured to use the so-called “cgroups v2” mechanism to enforce resource limits (which many HPC systems are). Let’s use this system to find out how much memory the raytracer actually needs. First, we set the memory limit back to 1 GB, i.e., to a configuration that is known to work.

Next, add these lines at the end of your job script:

BASH

echo -n "Total amount of memory used (in bytes): "

cat /sys/fs/cgroup/$(cat /proc/self/cgroup | awk -F ':' '{print $3}')/memory.peakLet’s break down what these lines do:

- The first line prints out a nice label for our peak memory output.

We use

-nto omit the usual newline thatechoadds at the end of its output. - The second line outputs the contents of a file (

cat). The path of this file starts with/sys/fs/cgroup, which is a location where the Linux kernel exports all the cgroups v2 information as files. - For the next part of the path we need the so-called “cgroup path” of

our job. To find out this path, we can use the

/proc/self/cgroupfile, which contains this path as the third entry of a colon-separated list. Therefore, we read the contents of this file (cat) and extract the third entry of the colon separated list (awk -F ':' '{print $3}'). Since we do this in$(...), Bash will place the output of these commands (i.e., the cgroup path) at this point. - The final part of the path is the information we actually want from

the cgroup. In out case, we are interested in

memory.peak, which contains the peak memory consumption of the cgroup.

When you submit your job and look at the output once it finishes, you will find a line like this:

[...]

Total amount of memory used (in bytes): 579346432

[...]So even though SLURM reported our job to only use 367.28 MB of memory, we actually used nearly 600 MB! With this measurement we can make an informed decision on how to set the memory limit for our job:

Run your job again with this limit to verify that it completes successfully.

So far we have tuned the time and memory limits of our job. Now let

us have a look at the CPU core limit. This limit works slightly

differently than the ones we looked at so far in the sense that your job

is not getting terminated if you try to use more cores than you have

allocated. Instead, the scheduler exploits the fact that multitasking

operating systems can switch out the process a given CPU core is working

on. If you have more active processes in your job than you have CPU

cores (i.e., CPU oversubscription), the operating system will

simply switch processes in and out while trying to ensure that each

process gets an equal amount of CPU time. This happens very fast, so you

can’t see the switching directly, but tools like htop will

show your processes running at less than 100% CPU utilization. Below you

can see a situation of four processes running on three CPU cores, which

results in each process running only 75% of the time.

CPU oversubscription can even be harmful to performance as all the switching between processes by the operating system can cost a non-trivial amount of CPU time itself.

Let’s try reducing the number of cores we allocate by reducing the number of MPI tasks we request in our job script:

Now we have a mismatch between the number of tasks we request and the

number of tasks we use in mpirun. However, MPI catches our

folly and prevents us from accidentally oversubscribing our CPU cores.

In the output file you see the full explanation

There are not enough slots available in the system to satisfy the 4

slots that were requested by the application:

./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer

Either request fewer procs for your application, or make more slots

available for use.

A "slot" is the PRRTE term for an allocatable unit where we can

launch a process. The number of slots available are defined by the

environment in which PRRTE processes are run:

1. Hostfile, via "slots=N" clauses (N defaults to number of

processor cores if not provided)

2. The --host command line parameter, via a ":N" suffix on the

hostname (N defaults to 1 if not provided)

3. Resource manager (e.g., SLURM, PBS/Torque, LSF, etc.)

4. If none of a hostfile, the --host command line parameter, or an

RM is present, PRRTE defaults to the number of processor cores

In all the above cases, if you want PRRTE to default to the number

of hardware threads instead of the number of processor cores, use the

--use-hwthread-cpus option.

Alternatively, you can use the --map-by :OVERSUBSCRIBE option to ignore the

number of available slots when deciding the number of processes to

launch.If we actually want to see oversubscription in action, we need to switch from MPI to multithreading. First, let us try without oversubscribing the CPU cores:

BASH

#SBATCH --ntasks=1

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task=4

# [...]

./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=4 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.pngThis works and if we look at the output of seff again we

get a baseline for our multithreaded job

[...]

CPU Utilized: 00:21:32

CPU Efficiency: 99.08% of 00:21:44 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:05:26

Memory Utilized: 90.85 MB

Memory Efficiency: 12.11% of 750.00 MBChallenge

Compare our measurements for 4 threads here to the measurements we made for doing the computation with 4 MPI tasks earlier. What metrics are similar and which ones are different? Do you have an explanation for this?

We can see that the CPU utilization time and the walltime are virtually identical to the MPI version of our job, while the memory utilization is much lower. The exact reasons for this will be discussed in the following episodes, but here is the gist of it:

- Our job is strongly compute-bound, i.e., the time our job takes is mostly determined by how fast the CPU can do its calculations. This is why it does not matter much for CPU utilization whether we use MPI or threads as long as both can keep the same number of CPU cores busy.

- MPI typically incurs an overhead in CPU usage and memory due to the need to communicate between the tasks (in comparison, threads can just share a block of memory without communication). In our raytracer, this overhead for CPU usage is negligible (hence the same CPU utilization time metrics), but there is a significant memory overhead.

Now let’s see what happens when we oversubscribe our CPU by doubling the number of threads without increasing the number of allocated cores in our job script:

BASH

./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=8 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.pngChallenge

If you cluster allows direct access to the compute nodes, try logging into the node your job is running on and watch the CPU utilization live using

(Note: Sometimes htop hides threads to make the process

list easier to read. This option can be changed by pressing F2, using

the arrow keys to navigate to the “Hide userlang process threads”,

toggling with the return key and then applying the change with F10.)

Compare the CPU utilization of the raytracter threads

with different total numbers of threads.

In the top right of htop you can also see a metric

called load average. Simplified, this is the number of

processes / threads that are currently either running or could run if a

CPU core was free. Compare the amount of load you generate with your job

depending on the number of threads.

You can see that the CPU utilization of each raytracer

thread goes down as the number of threads increases. This means, each

process is only active for a fraction of the total compute time as the

operating system switches between threads.

For the load metric, you can see that the load increases linearly with the number of threads regardless if they are actually running or waiting for a CPU core. Load is a fairly common metric to be monitored by cluster administrators, so if you cause excessive load by CPU oversubscription you will probably hear from your local admin.

Despite using twice the amount of threads, we barely see any

difference in the output of seff:

CPU Utilized: 00:21:29

CPU Efficiency: 98.85% of 00:21:44 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:05:26

Memory Utilized: 93.32 MB

Memory Efficiency: 12.44% of 750.00 MBThis shows that despite having more threads, the CPU cores are not performing more work. Instead, the operating system periodically rotates the threads running on each allocated core, making sure every thread gets a time slice to make progress.

Let’s see what happens when we increase the thread count to extreme levels:

BASH

./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=1024 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.pngWith this setting, seff yields

CPU Utilized: 00:26:45

CPU Efficiency: 99.07% of 00:27:00 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:06:45

Memory Utilized: 113.29 MB

Memory Efficiency: 15.11% of 750.00 MBAs we can see, our job is actually getting slowed down from all the switching between threads. This means, that for our raytracer application CPU oversubscription is either pointless or actively harmful regarding performance.

If CPU oversubscription is so bad, then why do most operating systems default to this behavior?

In this case we have a CPU bound application, i.e., the work done by the CPU is the limiting factor and thus dividing this work into smaller chunks does not help with performance. However, there are also applications bound by other resources. For these applications it makes sense to assign the CPU core elsewhere while the process is waiting, e.g., on a storage medium. Also, in most systems it is desireable to have more programs running than your computer has CPU cores since often only a few of them are active at the same time.

Multi-node jobs

So far, we have only used a single node for our job. The big advantage of MPI as a parallelism scheme is the fact that not all MPI tasks need to run on the same node. Let’s try this with our Snowman raytracer example:

BASH

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --nodes=2

#SBATCH --partition=<put your partition here>

#SBATCH --ntasks=4

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task=1

#SBATCH --mem=700M

#SBATCH --time=00:07:00

#SBATCH --output=snowman-stdout.log

#SBATCH --job-name=snowman

# Always a good idea to purge modules first to start with a clean module environment

module purge

# <put the module load commands for your cluster here>

mpirun -- ./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=1 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.png

echo -n "Total amount of memory used (in bytes): "

cat /sys/fs/cgroup$(cat /proc/self/cgroup | awk -F ':' '{print $3}')/memory.peakThe important change here compared to the MPI jobs before is the

--nodes=2 directive, which instructs Slurm to distribute

the 4 tasks across exactly two nodes.

You can also leave the decision of how many nodes to use up to Slurm by specifying a minimum and a maximum number of nodes, e.g.,

--nodes=1-3would mean that Slurn can assign your job either one, two or three nodes.

Let’s look at the seff report of our job once again:

[...]

Nodes: 2

Cores per node: 2

CPU Utilized: 00:21:32

CPU Efficiency: 98.78% of 00:21:48 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:05:27

Memory Utilized: 280.80 MB

Memory Efficiency: 20.06% of 1.37 GBWe can see that Slurm did indeed split up the job such that each of the two nodes is running two tasks. We can also see that the walltime and CPU time of our job are basically the same as before. Considering the fact that communication between nodes is usually much slower than communication within a node, this result is surprising at first. However, we can find an explanation in the way our raytracer works. Most of the compute time is spent on tracing light rays through the scene for each pixel. Since these light rays are independent from one another, there is no need to communicate between the MPI tasks. Only at the very end, when the final image is assembled from the samples calculated by each task, there is some MPI communication happening. The overall communication overhead is therefore vanishingly small.

How well your program scales as you increase the number of nodes depends strongly on the amount of communication in your program.

We can also look at the memory consumption:

[...]

Total amount of memory used (in bytes): 464834560

[...]As we can see, there was indeed less memory consumed on the node running our submit script compared to before (470 MB vs 580 MB). However, our method of measuring peak memory consumption does not tell us about the memory consumption of the second node and we have to use slightly more sophisticated tooling to find out how much memory we actually use.

In the course material is a directory

mpi-cgroups-memory-report that can help us out here, but we

need to compile it first:

Make sure you have a working MPI C Compiler (check with

which mpicc). It is part of the same modules that you need

to run the example raytracer application.

The memory reporting tool works by hooking itself into the

MPI_Finalize function that needs to be called at the very

end of every MPI program. Then, it does basically the same thing as we

did in the script before and checks the memory.peak value

from cgroups v2. To apply the hook to a program, you need to add the

path to the mpi-mem-report.so file we just created to the

environment variable LD_PRELOAD:

BASH

LD_PRELOAD=$(pwd)/mpi-cgroups-memory-report/mpi-mem-report.so mpirun -- ./SnowmanRaytracer/build/raytracer -width=1024 -height=1024 -spp=256 -threads=1 -alloc_mode=3 -png=snowman.pngAfter submitting this job and waiting for it to complete, we can check the output log:

[...]

[MPI Memory Reporting Hook]: Node r05n10 has used 464564224 bytes of memory (peak value)

[MPI Memory Reporting Hook]: Node r07n04 has used 151105536 bytes of memory (peak value)

[...]The memory consumption of the first node matches our previous result, but we can now also see the memory consumption of the second node. Compared to the first node the second node uses much less memory, however in total both nodes use slightly more memory than running all four tasks on a single node (610 MB vs 580 MB). This memory imbalance between the nodes is an interesting observation that we should keep in mind when it comes to estimating how much memory we need per node.

Tips for job submission

To end this lesson, we discuss some tips for choosing resource allocations such that your jobs get scheduled more quickly.

- Many clusters have activated the so-called backfill scheduler option in Slurm. This mechanism tries to squeeze low priority jobs in the gaps between jobs of higher priority (as long as the larger jobs are not delayed by this). In this case, smaller jobs are generally advantageous as they can “skip ahead” in the queue and start early.

- Using

sinfo -t idleyou can specifically search for partitions that have idle nodes. Consider using these partitions for your job if possible as an idle node will typically start your job immediately. - Different partitions might have different billing weights,

i.e., they might use different factors to determine the “cost” of your

calculation, which is subtracted from your compute budget or fairshare

score. You can check these weights using

scontrol show partition <partitionname> | grep TRESBillingWeights. The idea behind different billing weights is to even out the cost of the different resources (i.e., how many hours of memory use correspond to one hour of CPU use) and to ensure that using more expensive hardware carries an appropriate cost for the users. - Typically, it takes longer for a large slot to free up than it takes for several small slots to open. Splitting your job across multiple nodes might not be the most computationally efficient way to run it due to the possible communication overhead, but it can be more efficient in terms of scheduling.

- Slurm produces an estimate on when your job will be started which

you can check with

scontrol show job 35749406 | grep StartTime.

I’m not sure if this is the right section to discuss this…

- Your cluster might seem to have an enormous amout of computing resources, but these resources are a shared good. You should only use as much as you need.

- Resource requests are a promise to the scheduler to not use more

than a specific amount of resources. If you break your promise to the

scheduler and try to use more resources, terrible things will happen.

- Overstepping memory or time allocations will result in your job being terminated.

- Oversubscribing CPU cores will at best do nothing and at worst diminish performance.

- Finding the minimal resource requirements takes a bit of trial and error. Slurm collects a lot of useful metrics to aid you in this.

Content from Scheduler Tools

Last updated on 2025-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What can the scheduler tell about job performance?

- What’s the meaning of collected metrics?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to …

- Explain basic performance metrics.

- Use tools provided by the scheduler to collect basic performance metrics of their jobs.

Scheduler Tools

A scheduler performs important tasks such as accepting and scheduling jobs, monitoring job status, starting user applications, cleaning up jobs that have finished or exceeded their allocated time. The scheduler also keeps a history of jobs that have been run and how they behaved. The information that is collected can be queried by the job owner to learn about how the job utilized the resources it was given.

The seff tool

The seff command can be used to learn about how

efficiently your job has run. The seff command takes the

job identifier as an argument to select which job it displays

information about. That means we need to run a job first to get a job

identifier we can query SLURM about. Then we can ask about the

efficiency of the job.

seff may not be available

seff is an optional SLURM tool for more convenient

access to saact. It does not come standard with every SLURM

installation. Your particular HPC system may or may not provide it.

Check for it’s availability on your login nodes, or consult your cluster

documentation or support staff.

Other third party alternatives, e.g. reportseff, can be installed with default user permissions.

The sbatch command is used to submit a job. It takes a

job script as an argument. The job script contains the resource

requests, such as the amount of time needed for the calculation, the

number of nodes, the number of tasks per node, and so on. It also

contains the commands to execute the calculations.

Using your favorite editor, create the job script

render_snowman.sbatch with the contents below.

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --tasks-per-node=4

# Possibly a "module load ..." command to load required libraries

# Depends on your particular HPC system

mpirun -np 4 raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp=128 -alloc_mode=3Next submit the job with sbatch, and see what

seff says about the job with the following commands.

OUTPUT

Job ID: 309489

Cluster: bigiron

User/Group: usr123/grp123

State: COMPLETED (exit code 0)

Nodes: 1

Cores per node: 4

CPU Utilized: 00:07:43

CPU Efficiency: 98.93% of 00:07:48 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:01:57

Memory Utilized: 35.75 MB

Memory Efficiency: 0.20% of 17.58 GB (4.39 GB/core)The job script we created asks for 4 CPUs for an hour. After

submitting the job script we need to wait until the job has finished as

seff can only report sensible statistics after the job is

completed. The report from seff shows basic statistics

about the job, such as

- The resources the job was given

- the number of nodes

- the number of cores per node

- the amount of memory per core

- The amount of resources used

-

CPU Utilizedthe aggregate CPU time (the time the job took times the number of CPUs allocated) -

CPU Efficiencythe actual CPU usage as a percentage of the total available CPU capacity -

Job Wall-clock timethe time the job took from start to finish -

Memory Utilizedthe aggregate memory usage -

Memory Efficiencythe actual memory usage as a percentage of the total avaialable memory

-

Looking at the Job Wall-clock time it shows that the job

took just under 2 minutes. Therefore this job took a lot less time than

the one hour we asked for. This can be problematic as the scheduler

looks for time windows when it can fit a job in. Long running jobs

cannot be squeezed in as easily as short running jobs. As a result, jobs

that request a long time to complete typically have to wait longer

before they can be started. Therefore asking for more than 10 times as

much time as the job really needs, simply means that you will have to

wait longer for the job to start. On the other hand you do not want to

ask for too little time. Few things are more annoying than waiting for a

long running calculation to finish, just to see the job being killed

right before the end because it would have needed a couple of minutes

more than you asked for. So the best approach is to ask for more time

than the job needs, but not go overboard here. As the job elapse time

depends on many machine conditions, including congestion in the data

communication, disk access, operating system jitter, and so on, you

might want to ask for a substantial buffer. Nevertheless, asking for

more than twice as much time as job is expected to need, usually doesn’t

make sense.

Another thing is that SLURM by default reserves a certain amount of

memory per core. In this case the actual memory usage is just a fraction

of that amount. We could reduce the memory allocation by explicitly

asking for less by modifying the render_snowman.sbatch job

script.

Challenge

Edit the batch file to reduce the amount of memory requested for the

job. Note that the amount of memory per node can be requested with the

--mem= argument. The amount of memory is specified by a

number followed by a unit. The units can represent kilobtytes (KB),

megabytes (MB), gigabytes (GB). For the calculations we are doing here

100 megabytes per node is more than sufficient. Submit the job, and

inspect the efficiency with seff. What is the memory usage

efficiency you get?

The batch file after adding the memory request becomes.

#!/usr/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=01:00:00

#SBATCH --nodes=1

#SBATCH --tasks-per-node=4

#SBATCH --mem=100MB

# Possibly a "module load ..." command to load required libraries

# Depends on your particular HPC system

mpirun -np 4 raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp=128 -alloc_mode=3Submit this jobscript, as before, with the following command.

OUTPUT

Job ID: 310002

Cluster: bigiron

User/Group: usr123/grp123

State: COMPLETED (exit code 0)

Nodes: 1

Cores per node: 4

CPU Utilized: 00:07:43

CPU Efficiency: 98.09% of 00:07:52 core-walltime

Job Wall-clock time: 00:01:58

Memory Utilized: 50.35 MB

Memory Efficiency: 50.35% of 100.00 MB (100.00 MB/node)The output of seff shows that about 50% of requested

memory was used.

Now we see that a much larger fraction of the allocated memory has been used. Normally you would not worry too much about the memory request. Lately HPC clusters are used more for machine learning work loads which tend to require a lot of memory. Their memory requirements per core might actually be so large that they cannot use all the cores in a node. So there may be spare cores available for jobs that need little memory. In such a scenario tightening the memory allocation up could allow the scheduler to start your job early. How much milage you might get from this depends on the job mix at the HPC site where you run your calculations.

Note that the CPU utilization is reported as almost 100%, but this

just means that the CPU was busy with your job 100% of the time. It does

not mean that this time was well spent. For example, every parallel

program has some serial parts to the code. Typically those parts are

executed redundantly on all cores, which is wasteful but not reflected

in the CPU efficiency. Also, this number does not reflect how well the

capabilities of the CPU are used. If your CPU offers vector

instructions, for example, but your code does not use them then your

code will just run slow. The CPU efficiency will still show that the CPU

was busy 100% of the time even though the program is just running at a

fraction of the speed it could achieve if it fully exploited the

hardware capabilities. It is worth keeping these limitations of

seff in mind.

Good utilization does not imply efficiency

Measuring close to 100% CPU utilization does not say anything about how useful the calculations are. It’s merely stating, that the CPU was mostly busy with calculations, instead of waiting for data or running idle, waiting for other conditions to occur.

Good CPU utilization is only efficient, if it runs only “useful” calculations that contribute with new results towards an intended goal.

The seff command cannot give you any information about

the I/O performance of your job. You have to use other approaches for

that, and sacct may be one of them.

The sacct tool

The sacct command shows data stored in the job

accounting database. You can query the data of any of your previously

run jobs. Just like with seff you will need to provide the

job ID to query the accounting database. Rather than keeping track of

all your jobs yourself you can ask sacct to provide you

with an overview of the jobs you have run.

OUTPUT

JobID JobName Partition Account AllocCPUS State ExitCode

------------ ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- --------

309902 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309902.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309902.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0In the output every job is shown three times here. This is because

sacct lists one line for the primary job entry, followed by

a line for every job step. A job step corresponds to an

mpirun or srun command. The

extern line corresponds to all work that is done outside of

SLURM’s control, for example an ssh command that runs

something somewhere else.

Note that by default sacct only lists the jobs that have

been run today. You can use the --starttime option to list

all jobs that have been run since the given start date. For example, try

running

OUTPUT

JobID JobName Partition Account AllocCPUS State ExitCode

------------ ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- --------

308755 snowman.s+ STD-s-96h project_a 16 COMPLETED 0:0

308755.batch batch project_a 16 COMPLETED 0:0

308755.exte+ extern project_a 16 COMPLETED 0:0

308756 snowman.s+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

308756.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

308756.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309486 interacti+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 FAILED 1:0

309486.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309486.0 prted project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309489 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309489.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309489.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309902 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309902.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309902.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

309903.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0You may want to change the date of 2025-09-25 to

something more sensible when you work through this tutorial. Note that

some HPC systems may limit the range of such a request to a maximum of,

for example, 30 days to avoid overloading the slurm database with too

large requests.

With the job ID you can ask sacct for information about

a specific job as in

OUTPUT

JobID JobName Partition Account AllocCPUS State ExitCode

------------ ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- --------

310002 render_sn+ STD-s-96h project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.batch batch project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0

310002.exte+ extern project_a 4 COMPLETED 0:0Using sacct with the --jobs flag is just

another way to select which jobs we want more information about. In

itself it does not provide any additional information. To get more

specific data we need to explicitly ask for the information we want. As

SLURM collects a broad range of data about every job it is worth to

evaluate what the most relevant items are.

-

MaxRSS,AveRSS, or the Maximum or Average Resident Size Set (RSS). The RSS is the memory allocated by a program that is actually resident in the main memory of the computer. If the computer gets low on memory then the virtual memory manager can extend the apparently available memory by moving some of the data from memory to disk. This is done entirely transparently to the application, but the data that has been moved to disk is no longer resident in main memory. As a result accessing it will be slower because it needs to retrieved from disk first. Therefore if the RSS is small compared to the total amount of memory the program uses this might affect the performance of the program. -

MaxPages,AvePages, or the Maximum or Average number of Page Faults. These quantities are related to the Resident Size Sets. When the program tries to access data that is not resident in main memory this triggers a page fault. The virtual memory manager responds to a page fault by retrieving the accessed data from disk (and potentially migrating other data to disk to make space). These operations are typically costly. Therefore high numbers of page faults typically correspond to a significant reduction in the program’s performance. For example, the CPU utilization might drop from as high as 98% to as low as 2% due to page faults. For that reason some HPC machines are configured to kill your job if the application generates a high rate of page faults. -

AllocCPUSis the number of CPUs allocated for the job. -

Elapsedis the amount of wall clock time it took to complete the job. I.e. the amount of time that passed between the start and finish of the job. -

MaxDiskRead, the Maximum amount of data read from disk. -

MaxDiskWrite, the Maximum amount of data written to disk. -

ConsumedEnergy, the amount of energy consumed by the job if that information was collected. The data may not be collected on your particular HPC system and is reported as 0. -

AveCPUFreq, the average CPU frequency of all tasks in a job, given in kHz. In general the higher the clock frequency of the processor the faster the calculation runs. The exception is if the application is memory bandwidth limited and the data cannot be moved to processor fast enough to keep it busy. In that case modern hardware might throttle the frequency. This saves energy as the power consumption scales linearly with the clock frequency, but doesn’t slow the calculation down as the processor was having to wait for data anyway.

We can explicitly select the data elements that we are interested in. To see how long the job took to complete run

OUTPUT

Elapsed

----------

00:01:58

00:01:58

00:01:58Challenge

Request information regarding all of the above variables from

sacct, including JobID. Note that the

--format flag takes a comma separated list. Also note that

the result shows that more data is read than written, even though the

program generates and write an image, and reads no data at all. Why

would that be?

To query all of the above variable run

BASH

sacct --jobs=310002 --format=MaxRSS,AveRSS,MaxPages,AvePages,AllocCPUS,Elapsed,MaxDiskRead,MaxDiskWrite,ConsumedEnergy,AveCPUFreqOUTPUT

MaxRSS AveRSS MaxPages AvePages AllocCPUS Elapsed MaxDiskRead MaxDiskWrite ConsumedEnergy AveCPUFreq

---------- ---------- -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ------------ ------------ -------------- ----------

4 00:01:58 0

51556K 51556K 132 132 4 00:01:58 6.91M 0.72M 0 3M

0 0 0 0 4 00:01:58 0.01M 0.00M 0 3MAlthough the program we have run generates an image and writes that to a file, there is also a none zero amount of data read. The writing part is associated with the image file the program writes. The reading part is not associated with anything that the program does, as it doesn’t read anything from disk. It is instead associated with the fact that the operating system has to read the program itself and it’s dependencies to execute it.

Shortcomings

While seff and sacct provide a lot of

information it is still incomplete. For example, the information is

accumulated for the entire calculation. Variations in the metrics as a

function of time throughout the job are not available. Communication

between different MPI processes is not recorded. The collection of the

energy consumption depends on the hardware and system configuration at

the HPC center and might not be available. We are also often missing

reliable measurements for I/O via the interconnect between nodes and the

parallel file system.

So while we might be able to glean some indications for different types of performance problems, for a proper analysis more detailed information is needed.

Summary

This episode introduced the SLURM tools seff and

sacct to get a high level perspective on a job’s

performance. As these tools just use the statistics that SLURM collected

on a job as it ran, they can always be used without any special

preparation.

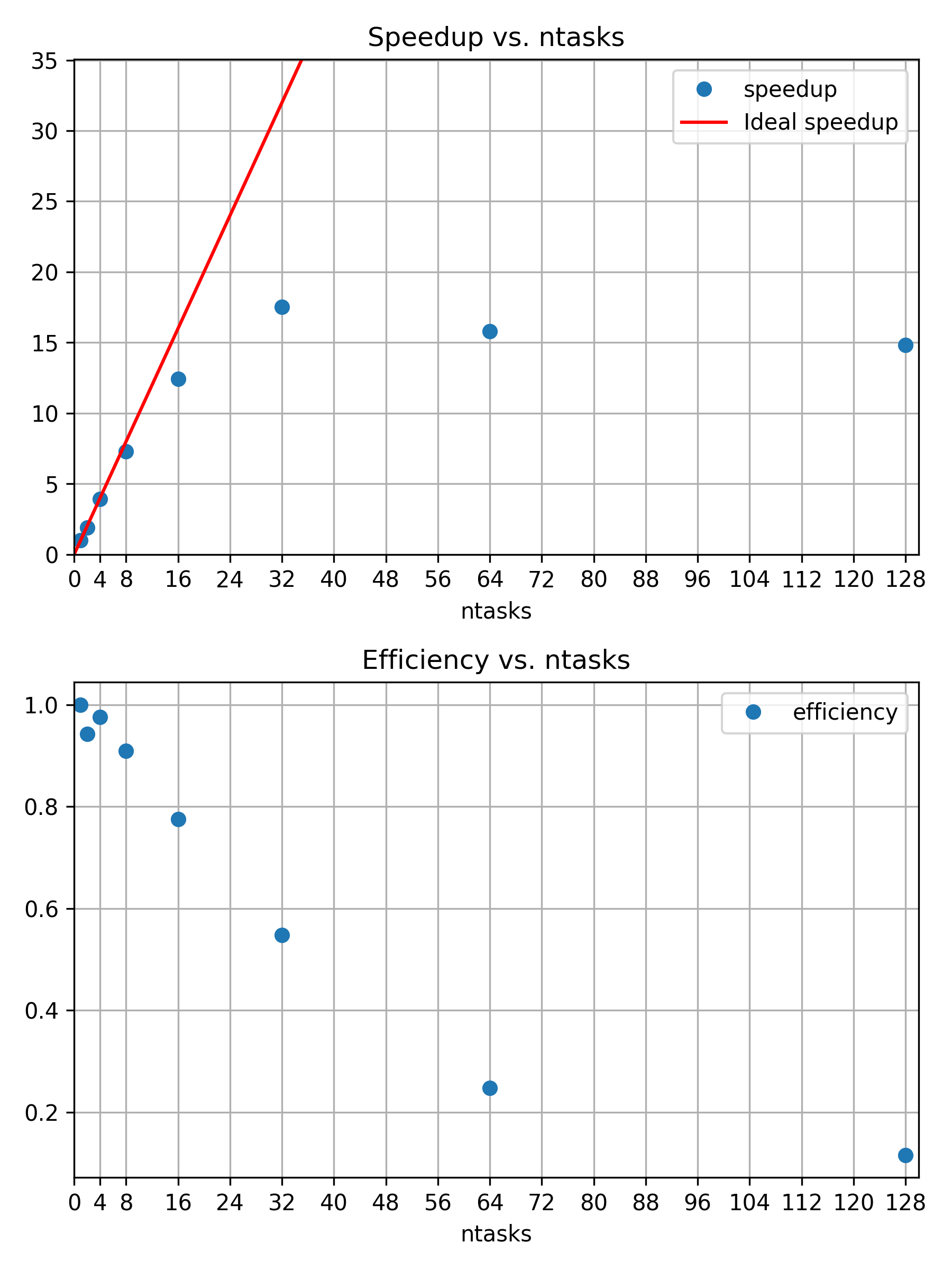

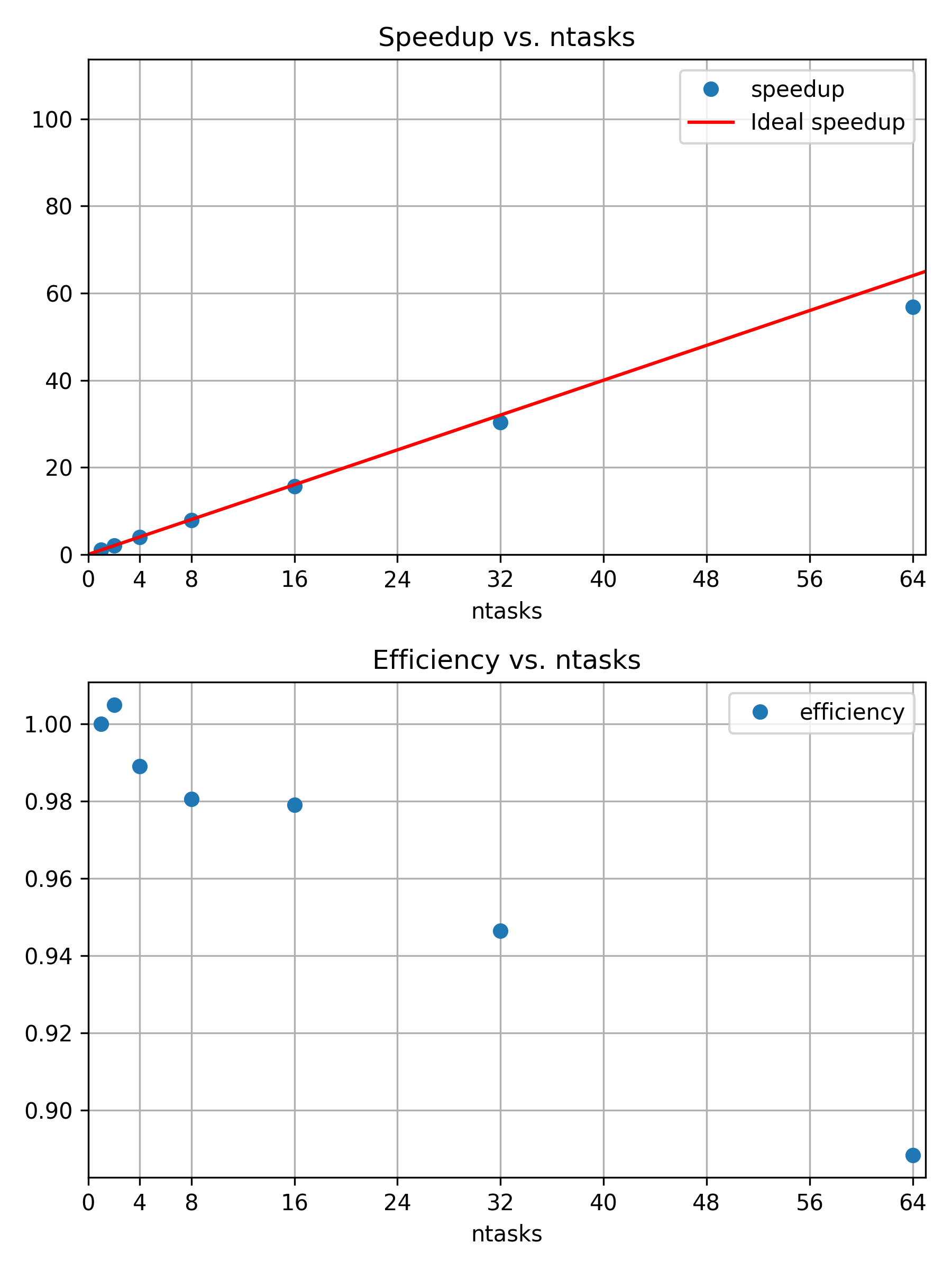

Challenge

So far we have considered our initial calculation using 4 cores. To

run the calculation faster we could consider using more cores. Run the

same calculation on 8, 16, and 32 cores as well. Collect and compare the

results from sacct and see how the job performance

changes.

The machine these calculations have been run on has 112 core per node. So we can double the number of cores from 4 until 64 and stay within one node. If we go to two nodes then some of the communication between tasks will have to go across the interconnect. At that point the performance characteristics might change in a discontinuous manner. Hence we try to avoid doing that.

Alternatively you might scale the calculation across multiple nodes, for example 2, 4, 8, 16 nodes. With 112 cores per node you would have to make sure that the calculation is large enough for such a large number of cores to make sense.

Create running_snowmen.sh with

#!/usr/bin/bash

for nn in 4 8 16 32; do

id=`sbatch --parsable --time=00:12:00 --nodes=1 --tasks-per-node=$nn --ntasks-per-core=1 render_snowman.sh`

echo "ntasks $nn jobid $id"

doneCreate render_snowman.sh with

#!/usr/bin/bash

# Possibly a "module load ..." command to load required libraries

# Depends on your particular HPC system

export START=`pwd`

# Create a sub-directory for this job if it doesn't exist already

mkdir -p $START/test.$SLURM_NTASKS

cd $START/test.$SLURM_NTASKS

# The -spp flag ensures we have enough samples per ray such that the job

# on 32 cores takes longer than 30s. Slurm by default is configured such

# that job data is collected every 30s. If the job finishes in less than

# that Slurm might fail to collect some of the data about the job.

mpirun -np $SLURM_NTASKS raytracer -width=800 -height=800 -spp 1024 -threads=1 -alloc_mode=3 -png=rendered_snowman.pngNext we submit this whole set of calculations

producing

OUTPUT

ntasks 4 jobid 349291

ntasks 8 jobid 349292

ntasks 16 jobid 349293

ntasks 32 jobid 349294After the jobs are completed we can run

BASH

sacct --jobs=349291,349292,349293,349294 \

--format=MaxRSS,AveRSS,MaxPages,AvePages,AllocCPUS,Elapsed,MaxDiskRead,MaxDiskWrite,ConsumedEnergy,AveCPUFreqto produce

OUTPUT

MaxRSS AveRSS MaxPages AvePages AllocCPUS Elapsed MaxDiskRead MaxDiskWrite ConsumedEnergy AveCPUFreq

---------- ---------- -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ------------ ------------ -------------- ----------

4 00:09:35 0